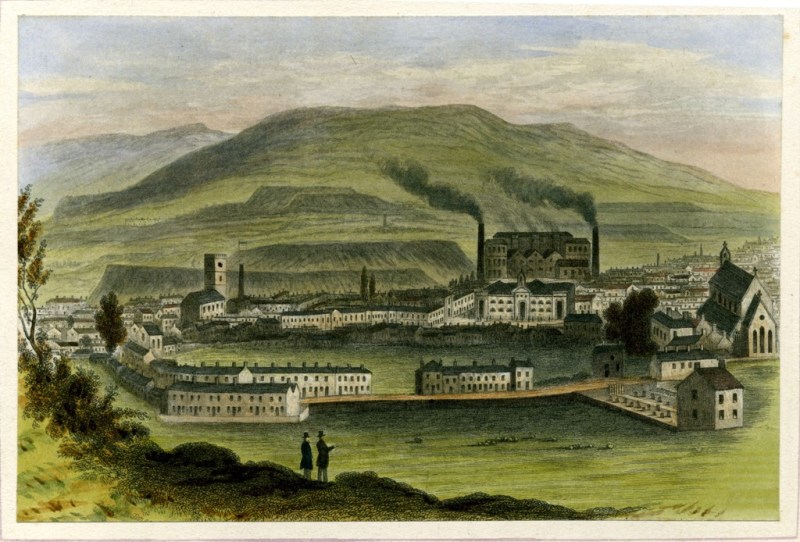

We continue our serialisation of the memories of Merthyr in the 1830’s by an un-named correspondent to the Merthyr Express, courtesy of Michael Donovan.

Now it always occurs to me that the doctoring system is a remainder of what in other cases would be called the truck system. Pray understand, I know how careful and skilful medical men are generally, and how admirably they perform their duties, yet there is always the thought that the system does not always co-ordinate with those general principles adopted in other things.

My own conviction is that truck in the early age of Merthyr was actually a necessity. When the works really began they were small, and no certainty of continuance. I am well aware of attempts that have been tried in various systems to alter it, but the system seems too firmly rooted to be altered for some time at least. An experiment in the adoption of a another method is, I believe, now being tried.

After a while Plymouth had Mr Probert (who by the bye, had been an assistant of Mr Russell), and so remained until his death, I think, but yet doubt that he resigned previously. Penydarren had Mr John Martin, and Mr Russell retained Dowlais, but it passed into the hands of his nephew Mr John Russell, for some time, and on his leaving Dr John Ludford White came to Dowlais.

This gentleman married a niece of Mr Wm. Forman, of the firm of Thompson and Forman, Cannon House, Queen Street, London, and after some years moved to Oxford, with the intention, it was said, of taking higher degrees. Dr White obtained the appointment through the recommendation of the London physician of Sir J John Guest, and in order that an accurate knowledge of the requirements might be, had visited Dowlais to see for himself. I remember him there, and an incident followed that will be mentioned when Dowlais is visited which will show the kind-heartedness of Sir John, and I hope also to mention one demonstrating his decision of character and another where I saw him weep.

We now return to Mr Russell’s surgery. A little further down, on the other side was Adullam (sic) Chapel, and cottages thence to the road to Twynyrodyn, while on the same side as Mr Russell’s was the way from the High Street, John Street by name, cottages somewhat irregular. The old playhouse also stood here; yes reader. It was a stone and mortar structure, and was for a long time unused.

Further on there was the Fountain Inn, between which and the Glove and Shears the road passed to Dowlais over Twynyrodyn, Pwllyrwhiad etc, but we cross and a few yards brings me to what was the boundary wall of Hoare’s garden, which continued down to where the line to Dowlais is now.

It has been my pleasure to see many gardens, but in all my experience I never saw one kept in such trim as this. Upon its being taken for the railway, Hoare started a garden and public house, if I remember well, at Aberdare Junction. Owing to the Taff Vale Company not allowing anyone to cross the line, a very long way around became a necessity to get there, and he did not do as well as anticipated or (I think) deserved.

Lower down the tramroad were some cottages on the right hand side, in one of which, adjoining the Shoulder of Mutton, a cask of powder exploded. It was kept under the bed upstairs for safety, and, lifting the roof off its walls, it fell some dozen yards away. The roof was covered with the thin flagstones often used and very little damaged. No one was fatally injured but one or two were injured, and altogether it was a wonderful escape. Moral: Do not keep a cask of explosive material upstairs under the bed!

To be continued at a later date……

Unlike many other chapels in Merthyr, Adulam was one of those chapels frequented by working class worshipers; its membership did not include an array of financial benefactors and throughout its history struggled to maintain its religious survival. Following the death of Rev Daniel T Williams in 1876, Adulam could not afford to pay for a new minister until 1883 when Rev D C Harris became minister. One of the first things he did on becoming minister was to set about alleviating the debt on the chapel. In 1884 he sent out appeals for aid to relieve Adulam’s financial burden to every household in the area – see above right. It is interesting to note that the name of the chapel is spelt in the English way with two ‘L’s rather than the more usual Welsh way with a single ‘L’.

Unlike many other chapels in Merthyr, Adulam was one of those chapels frequented by working class worshipers; its membership did not include an array of financial benefactors and throughout its history struggled to maintain its religious survival. Following the death of Rev Daniel T Williams in 1876, Adulam could not afford to pay for a new minister until 1883 when Rev D C Harris became minister. One of the first things he did on becoming minister was to set about alleviating the debt on the chapel. In 1884 he sent out appeals for aid to relieve Adulam’s financial burden to every household in the area – see above right. It is interesting to note that the name of the chapel is spelt in the English way with two ‘L’s rather than the more usual Welsh way with a single ‘L’.